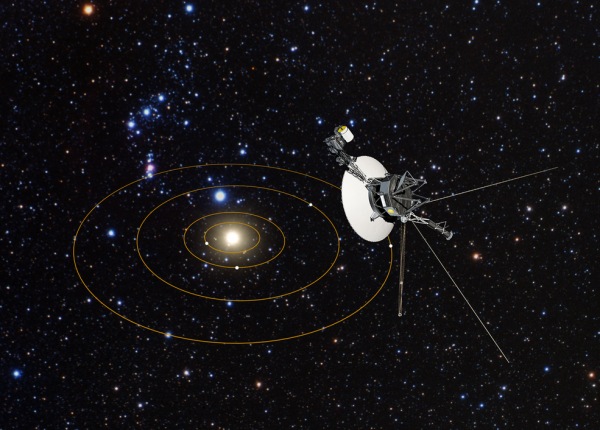

NASA’s two voyager spacecraft are currently gliding through previously unexplored territory beyond our Solar System while simultaneously measuring the interstellar medium that scientists are still trying to learn more and more about. Before both the spacecraft run out of juice (read: electric power), NASA is making sure that the data collected by the iconic Hubble space telescope help astronomers figure out the nature of the environment which Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 will travel through.

A preliminary analysis of the observational data from Hubble presents the evidence of a rich and complex interstellar ecology with clouds of hydrogen laced with various other elements. Simply put, the Hubble data, together with the data sent by the Voyagers, is also giving a glimpse into how the Sun has been traveling through interstellar space.

“This is a great opportunity to compare data from in situ measurements of the space environment by the Voyager spacecraft and telescopic measurements by Hubble,” said study leader Seth Redfield of Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut.

“The Voyagers are sampling tiny regions as they plow through space at roughly 38,000 miles per hour. But we have no idea if these small areas are typical or rare. The Hubble observations give us a broader view because the telescope is looking along a longer and wider path. So Hubble gives context to what each Voyager is passing through.”

Voyager 1 is currently 13 billion miles away from Earth, making it the farthest man-made object ever built. In another 40,000 years or so, the spacecraft will no longer be operational and won’t be able to gather new data. By then, it will reach somewhere within 1.6 light-years of the star Gliese 445, in the constellation Camelopardalis.

Meanwhile, its twin the Voyager 2, currently 10.5 billion miles from Earth, will be within 1.7 light years from the star Ross 248 in approximately 40,000 years from now.